Q. I found this crude copper and brass letter opener on eBay. The reason I purchased it is that I remembered seeing an identical form in The Craftsman magazine. I poured through the magazines and found the image in the November 1907 issue in an article explaining how to make your own metal pieces. Was this a common form, or was this possibly a piece designed from that Craftsman article? If so, do you think this is an attempt at following the directions and making the piece? Do many examples of early Craftsman do-it-yourself pieces exist?

Mark Winger

Syracuse, N.Y.

Q. Recently I purchased this candlestick and the two supporting photos on eBay. The candlestick is a beautiful design, made from somewhat lightweight

Q. Recently I purchased this candlestick and the two supporting photos on eBay. The candlestick is a beautiful design, made from somewhat lightweight

copper stock. There is very little hammering involved. I have included a scan of the back of the images as well (see page 43). On the back of the photo, the stick is identified only as being made by “Aunt Nettie.” What added extra appeal for me was that the candlestick appears in this vintage “still life” photo. I also like the photo of the two ladies (though I don’t know which one Aunt Nettie is). Have you ever heard of or come across other pieces identified as being made by Aunt Nettie, or seen any of the other pieces pictured? Could she have been part of a guild?

Gary Jones

Rochester, N.Y.

Mark and Gary, congratulations on your eBay finds. It appears you’ve found a couple of well-made metal pieces by true Craftsman do-it-yourselfers. This is an area that can be confusing for collectors, so I’m glad for this opportunity to shed some light on it.

The revival of the American Arts and Crafts movement has already surpassed the length of time the original period flourished. Both periods were driven by a world that was suddenly moving too fast; as a society, we discovered an appreciation for the simpler things—handmade things made of natural materials. Arts and Crafts enthusiasts wanted to simplify their surroundings through the things they live with; to have nothing in their homes, as William Morris advised, that wasn’t useful or beautiful. That sentiment is alive and well today. To some, this means building collections of objects and art that enhance their lives; others get even greater satisfaction by creating something beautiful and useful with their own hands.

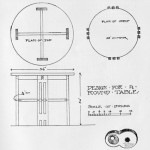

In the early part of the last century, books and publications like Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman gave DIYers food for the soul. He published plans for making many useful pieces of furniture similar to those found in the Stickley catalog (note I said similar; the master never gave out plans for his production pieces). Today, there are countless sources for the DIYer, including YouTube instruction, but many Arts and Crafts enthusiasts (like you, Mark) still turn to The Craftsman as the ultimate DIY source.

In the early part of the last century, books and publications like Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman gave DIYers food for the soul. He published plans for making many useful pieces of furniture similar to those found in the Stickley catalog (note I said similar; the master never gave out plans for his production pieces). Today, there are countless sources for the DIYer, including YouTube instruction, but many Arts and Crafts enthusiasts (like you, Mark) still turn to The Craftsman as the ultimate DIY source.

Do-It-Yourself projects were promoted heavily during the period. In the June 1908 issue of The Craftsman, for example, there was a six-page article on producing sideboards, stands and metal- work projects. The philosophy of living a healthier life through the art of the craft even spread through our schools. (I remember pounding a sheet of copper into an ashtray—that’s right, an ashtray.) Many DIYers find these plans as inspiring today as they were a century ago.

Do-It-Yourself projects were promoted heavily during the period. In the June 1908 issue of The Craftsman, for example, there was a six-page article on producing sideboards, stands and metal- work projects. The philosophy of living a healthier life through the art of the craft even spread through our schools. (I remember pounding a sheet of copper into an ashtray—that’s right, an ashtray.) Many DIYers find these plans as inspiring today as they were a century ago.

As a gallery owner who specializes in the American Arts and Crafts period, I have many DIYers come through our doors. Two come to mind who have become good friends. The first, Eamon Lee, a very talented local chef who loves Arts and Crafts style and working with wood, sometimes comes to the gallery to take measurements from a Stickley settle or a Limbert chair. I’ve helped him choose designs he could build in his own wood shop where he creates the majority of what he and his fiancé live with. In return, he built me a magnificent bamboo fly rod!

The second is Todd Conover, a professor at Syracuse University who became interested in metalsmithing. He started hammering copper, creating lamps, bowls and jewelry, incorporating acid-etched designs and enamel, all in his basement workshop; as you can see, he’s gotten quite good at it. In fact, he donated the magnificent clock pictured here to the Arts and Crafts Society of Central New York for a fundraising auction; it fetched more than several hundred dollars.

Now on to the questions:

Mark, your knife is a very nice find—I commend you on your detective work! I think it’s quite unusual to find a piece this close to an illustrated project example. Over the 30-plus years I have been dealing with Arts and Crafts, I have seen examples that I suspected were projects, but none this close. This design, as others published in The Craftsman, were not blueprinted plans of the objects and furniture produced by Mr. Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops. I suspect he was careful to change the details and/or the dimensions enough to not be exact replicas of his commercial designs. Along with his furniture plans, he even gave the DIYer the option of buying Craftsman Workshops hardware to finish it off.

Mark, your knife is a very nice find—I commend you on your detective work! I think it’s quite unusual to find a piece this close to an illustrated project example. Over the 30-plus years I have been dealing with Arts and Crafts, I have seen examples that I suspected were projects, but none this close. This design, as others published in The Craftsman, were not blueprinted plans of the objects and furniture produced by Mr. Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops. I suspect he was careful to change the details and/or the dimensions enough to not be exact replicas of his commercial designs. Along with his furniture plans, he even gave the DIYer the option of buying Craftsman Workshops hardware to finish it off.

Gary, I love the design of this candlestick. The fact that the gauge of copper may be thin and produced with few hammer marks doesn’t bother me at all. I like it when an object’s creation shows through in the finished product and is not overly decorated to look handmade. It is really wonderful that the photos stayed with the stick after all these years.

Gary, I love the design of this candlestick. The fact that the gauge of copper may be thin and produced with few hammer marks doesn’t bother me at all. I like it when an object’s creation shows through in the finished product and is not overly decorated to look handmade. It is really wonderful that the photos stayed with the stick after all these years.

I have done some research on Aunt Nettie, to no avail. The candlestick (and perhaps the other items in the photo) may have been crafted as her personal hobby, which may be why the picture was taken. How many of us have been compelled to take a photo of our own proud creations?). This could very well be a good example of someone who felt the urge to produce pieces for her own satisfaction. And it’s one of those rare examples when period images enhance the object’s desirability. One thing I can say is that meeting Aunt Nettie has been a pleasure!

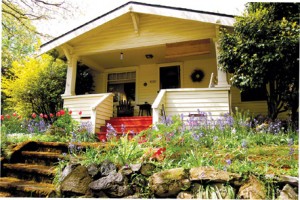

Atascadero, Calif., Yvonne Smith

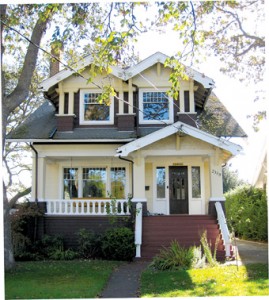

Atascadero, Calif., Yvonne Smith Long Beach, Calif., Lisa and Paul Harris

Long Beach, Calif., Lisa and Paul Harris Seattle, Wash., Bruce Parker and Vinita Sidhu

Seattle, Wash., Bruce Parker and Vinita Sidhu Chicago, Ill., Patrick Falso and Matthew Mika

Chicago, Ill., Patrick Falso and Matthew Mika Chicago, Ill., Peggy and John Bradley

Chicago, Ill., Peggy and John Bradley Murrysville, Pa., Steve and Vicky Richards

Murrysville, Pa., Steve and Vicky Richards Newton, Mass., Debbie Kurlansky-Winer

Newton, Mass., Debbie Kurlansky-Winer Uxbridge, Ontario, Rebecca Gower and Craig McLean

Uxbridge, Ontario, Rebecca Gower and Craig McLean BUNGALOW FEATURES

BUNGALOW FEATURES