THE STORY OF Phoenix’s Orpheum Theatre—which opened in January 1929, skirted demolition in the 1980s and was restored to its original splendor in the mid-1990s — follows the arc of Phoenix’s history through nearly eight decades, from the glory days of the city’s boom years in the twenties, through the depression, to Post–World War II suburban growth and urban abandonment, and finally to the renaissance of a vibrant downtown core over the past decade.

The Orpheum’s survival is not just a small miracle of historic preservation accomplished through an episode of cul-tural, civic and political imagination. It can also be seen as a monument to the age of vaudeville, which the social histo-rian Robert Snyder has called “the biblical era of twentieth-century American show business.”

Vaudeville’s stars, Snyder writes, “invigorated early radio, film, and television. Its format, a series of acts strung together, was transplanted to radio and television variety shows. Its theater circuits spawned chains of movie theaters. Its mass au-dience — constructed by calculating entrepreneurs, assembled in public, dynamically varied in its composition, signifi-cantly urban in its origins, knowledgeable and vocal in its demands — was the defining element of American popular culture for the first half of the twentieth century…

“Although vaudeville is now part of a receding past, in its history we can glimpse both a world we have lost and the embryonic forms of enduring patterns in American culture.”

PALACE IN THE DESERT

Phoenix’s Orpheum was one of the last in the legendary string of theater “palaces” built across the U.S. to present vaudeville shows produced by the Orpheum Circuit, which originated in New York City in the 1890s. Built just as vaude-ville was being eclipsed by the movies, the Phoenix Orpheum proved durable and flexible enough to adapt to the rise of motion pictures as the dominant American entertainment medium. Writing in The Arizona Republic in 2004, Cathy Creno captured the atmosphere of the city when the Orpheum ap-peared on the scene.

“Flappers, vaudeville, Buck Rogers and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. were all the rage when the Orpheum Theatre opened in January 1929.

“Silent pictures were on their way out, the Great Depression had yet to hit. And Phoenix was finally on the map—having grown from an isolated farming community to a budding city with streetcars, a major railway line and a population of 49,000.

“The town’s mood was boisterous and boosterish.

“‘Phoenix fastest growing city of size in country,’ boasted a headline in The Arizona Republican on Jan. 5, the day the Orpheum opened.

“Home builders developing the ritzy Encanto-Palmcroft neighborhood put ads in newspapers nationwide, urging Easterners to come west and buy an ‘estate’ with an English Tudor– or Spanish Colonial–style home.

“Encanto Park was still a farm field. But big buildings—a new city hall and county courthouse, Hotel Westward Ho, the San Carlos Hotel and the Luhrs Tower—were springing up just a few miles away.

“Probably none was greeted with more fanfare than the Orpheum, built at Second Avenue and Adams by Harry Nace and J.E. Rickards…

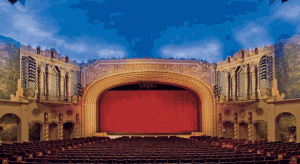

“Newspapers called the $750,000 movie palace the most luxurious theater west of the Mississippi. Patrons lined up for blocks—not only for movies and vaudeville shows but for the theater’s chilled, purified air and an opportunity to see projected clouds and stars from what appeared to be the courtyard of a 15th-century Moorish palace.”

State of the Art

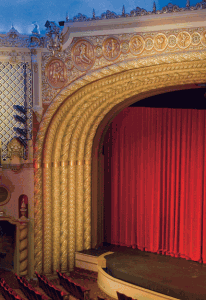

The new theater was “state of the art” for its time. The audience chamber was designed to create the illusion of sitting in the courtyard of a Spanish villa, beneath a sky that changed from golden sunset to starry night, with views of a distant landscape above the sidewalls. Ornate plaster work inside and out was done in Spanish Medieval and Baroque style, with guilt “ropes” arching over the stage.

Zodiac designs in the lobby door panels, a peacock design on the circular staircase, and colorful murals complemented intricately detailed arches, niches and columns in the lobbies.

Over the next 20 years, during the heyday of Hollywood films, going to the movies to see the stars of the era perform in the defining genres of Hollywood’s golden age—westerns, film noir, screwball comedies, musicals, historical adventures—was how most Americans got their entertainment.

The newsreels of the day vividly—often feverishly—portrayed the national experience through Depression, war, “the Bomb,” the Red Scare and the early years of the Cold War. Producers of “educational” short films found opportunities to slake the public thirst for guidance on everything from teenage dating to the evils of marijuana. For dessert, there were the imperishable Warner Brothers cartoons.

But just as the movies had eaten away at vaudeville, television steadily eroded the audience for movies at the same time that the suburbs were drawing people out of the central city. Downtown Phoenix’s center of gravity, once neatly bisected by Central Avenue, began moving east, leaving the Orpheum and the rest of the area west of Central more or less an afterthought.

In the end, that turned out to be one of the key circumstances leading to the theater’s salvation. While redevelopers worked their way east, swallowing up the old Fox and Rialto theaters, the Orpheum (after a brief interlude as the “Palace West” under the ownership of Broadway theater producer James Nederlander) took on a new life catering to Latino movie audiences.

But over the years, the theater’s owners had all but tarred the buildings elaborate interior spaces. The impressive wall murals were painted black, four of the seven proscenium “ropes” were removed to widen the stage, and much of the fabulous lobby and interior detail had been painted neutral.

Friends

That is where things stood through the 1970s and into the ’80s, when the threat that the theater might be bought as the site for a new theater gained momentum. And that is when the Phoenix Junior League sought, and found, enough community support to persuade the city to buy the theater to allay the immediate threat of demolition, with the idea that it might eventually be restored. It was as if the city had heeded the warning Sophie Tucker, “the last of the red hot mamas,” belted out to a wavering lover in the bluesy 1910 ballad “Some of These Days” —

Some of these days,

Oh, you’ll miss me, honey.

Some of these days,

You’re gonna be so lonely.

Then-Mayor Terry Goddard and a newly formed historic preservation task force embraced the idea, and in 1984 the city bought the theater for $1.5 million. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places the following year.

In 1985, to celebrate its 50th anniversary, the Junior League of Phoenix donated $50,000 for lobby restoration and an endowment. To raise public support and encourage private-sector donations, the League pledged an additional $150,000 when it established the Orpheum Theatre Foundation two years later.

In 1990, then-Mayor Paul Johnson and the Phoenix City Council made the inspired decision to incorporate the Orpheum restoration into the construction of a new city hall to be built on the south half of the theater’s block. The modern, 20-story city hall building became like a mother to a refurbished Orpheum, sharing water, power, air conditioning and other essential facilities.

Begun in 1994, the restoration was completed in 1997 at a cost of $14 million. Since then, the Orpheum has succeeded as a modern theater capable of handling anything Broadway sends its way. Its marquee again announces the names of first-class productions, drawing thousands of visitors to a vibrant downtown venue, lonely no more.

For their contributions to this article, we are indebted to the Friends of the Orpheum Theatre and to the writers who researched and synthesized the theater’s history leading up to its reopening in 1997. Chaunci Aeed, an original Junior League member of the Friends, has been especially helpful. Robert W. Snyder’s captivating history of vaudeville, Voices of the City: Vaudeville and Popular Culture in New York (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989), was reissued in paperback by Ivan R. Dee in 2000. To learn more about the Orpheum, visit friendsoftheorpheumtheatre.org.

Pin It