We’d thought we’d share some photos that include great use of Wallpaper.

Hope you enjoy them.

Hope everyone is having a great start to the new year!

This preview shows almost all the photographs in the book The Bungalow, written by Paul Duchscherer and Douglas Keister.

Click here to visit Doug Keister’s site

It’s that time of the year again. We’d love to see what you’ve done with your bungalow this holiday season, and to get you started here are some of our favorites.

1928 Craftsman brick bungalow located in Normal, IL

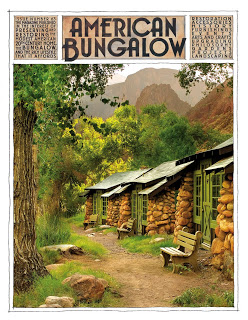

Preservation, restoration and heritage are the major themes of the newest issue of American Bungalow. For those who aren’t subscribers or haven’t yet picked up a copy from their favorite dealer or newsstand, here’s a preview.

The story of Phoenix’s historic Orpheum Theatre—which opened in January 1929, skirted demolition in the 1980s and was restored to its original splendor in the mid-1990s—follows the arc of Phoenix’s history through nearly eight decades, from the glory days of the city’s boom years in the twenties, through the Great Depression, to Post–WW II suburban growth and urban abandonment, and finally to the renaissance of a vibrant downtown core over the past decade.

“Oh, You’ll Miss Me, Honey: When Phoenix Changed Its Mind and Saved the Orpheum,” says that the restoration, completed in 1994, is not just a monument to the age of vaudeville but also “a small miracle of historic preservation accomplished through an episode of cultural, civic and political imagination.” The story is online here, but to see how Alexander Vertikoff’s photos capture the restoration in all its extravagant, over-the-top glory, you’ll have to pick up the magazine; the Web just can’t do justice to this grand theater palace.

“Light, River, Rock, Tree: Phantom Ranch’s Elemental Music” is a stunning portrait of Mary Jane Colter’s Phantom Ranch, a rustic cabin resort on the floor of the Grand Canyon. The article is the first in a new series on the melding of European-American Arts and Crafts, Spanish Missionary and Native-American Indian cultures that took place in the American Southwest in the decades bridging the 1880s and the 1920s, giving rise to the “Southwest style.”

Drawing heavily on Native American and Spanish Mission arts, crafts and building designs, the Southwest style’s emergence coincided with the bungalow era, and Southwest artifacts and furnishings soon became the decor of choice for bungalow living.

Craftsman-era gems

Three residential gems from the Craftsman era highlight regional variations in early-20th-century design. One, in the Laurelhurst neighborhood of Portland, Ore., has simply been well treated and carefully preserved. The other two, in Kansas City, Mo., and San Diego, Calif., have been meticulously restored—in K.C. over 15 years and in San Diego over 40.

“If you don’t look too closely,” writes the author of the Portland story, “the 1915 home, with its high square center flanked on both sides by lower, projecting front blocks, looks as though it could have been built around 1955—either that, or perhaps centuries ago, in Moorish Spain. The abundance of leaded and stained glass gives it away, though, as do the elaborate interior trim and a built-in buffet made to rival the most well-appointed Arts and Crafts homes.

“Nancy and Victor Rhodes, who bought the house as a starter home in 1973, have now settled into it as their place of retirement. And over the three and a half decades they’ve lived there, they’ve come not just to love it but to know it, patiently piecing together its history.”

In Kansas City, the popular local TV news reporter Stan Carmack had begun restoring a historic 1910 Hyde Park limestone Craftsman foursquare when he owned it briefly in the 1970s. In 1994, Jae McKeown and Robin Rusconi bought it and began the work of completing the restoration. Their meticulous craftsmanship and discerning taste in period furnishings have given the century-old parkside home a new lease on life that would make its architect, the prolific Clarence Erasmus Shepard, proud.

And in San Diego, when Carolyn and Tom Owen-Towle bought a gracefully proportioned but somewhat faded Craftsman home in the city’s historic Bankers Hill neighborhood in 1978, they thought colorful paint and great-looking rugs were all it would take to bring it back to life. But the couple, then new co-ministers (and now ministers emeriti) at San Diego’s First Unitarian Universalist Church, asked local architectural historian and preservationist Rurik Kallis to restore a damaged window.

Kallis complied, then suggested restoring the window seat beneath it … and then the entire room. When they saw the result, they realized they had begun a journey of restoration they would have to complete, no matter how long it took. “We felt a responsibility—almost a calling, really—to reclaim that beauty,” Carolyn says. Forty years later, they’ve brought it all back home. And because Carolyn is the daughter of the famed California artist, arts educator and curator Millard Owen Sheets, the stately yet festive home today houses a substantial collection of Sheets’s own luminous paintings and of the world art he and Carolyn’s mother collected during their decades of travel abroad.

Finally, in this issue’s “From Our Friends” essay, San Antonio architect J. Douglas Lipscomb, AIA, argues that the kind of design excellence Vitruvius advocated during the reign of Augustus Caesar sometime before 27 B.C.—and that is still the foundation of successful and healthy communities today—can be found in our modest American bungalows, which have proved durable, adaptable and filled with delight.

“Bungalows!? Why on earth would anybody in his right mind want to publish a magazine about those horrid little houses? They’re exactly the kind of houses we’re trying to get rid of!”

These words, thrown in my face like a slapstick pie by a squat, scowling person at a national preservation conference in 1990, were both startling and sobering. We had struggled to produce the first issue of our magazine and scraped together enough money to debut American Bungalow at the conference, 3,000 miles from home, only to find that there were preservationists like the pie thrower who considered the bungalow to be such an unsightly blemish on the fair countenance of America’s architectural heritage that their instant removal was justified. Fortunately, there was a larger contingent at the conference who applauded and cheered us on, delighted to see a publication devoted to a house type that they considered to be sensible, efficient and stylish, a long-neglected icon of American self-reliance. With the catcalls drowned out by the standing ovation, we came away feeling reinforced, endorsed by experts and more determined than ever to help these cozy if common little houses step into the limelight they deserved.

With no funds to advertise in those days, our only option to gain publicity for the magazine was to send out press releases to newspapers large and small across the country, and that’s exactly what we did next. The results were surprisingly gratifying. Reporters from cities large and small were quick to announce that the lowly bungalows that nested in their city’s decaying old section might be enjoying a comeback, and we were pleased to see the optimistic story repeated in papers from all over the country. That was in the early 1990’s, a time when inflated property values were releasing hot air at an alarming rate and forcing America’s high-flying ideas about extravagant housing to fall back to earth, much as we’re experiencing today.

These memories came to mind because of the frequency with which I see similar articles appearing in print and on the Internet lately. Across the country, a new generation of reporters, with a detectable twang of discovery in their words, proclaims that the efficient, stylish bungalow may be a new trend—a sensible option to the McMansions of the past decades—and a possible remedy to America’s housing problems. The idea has resurfaced that new urbanism might not be necessary when there is a plethora of bungalow neighborhoods in almost every American city, waiting to be appreciated and complete with local shopping, sidewalks and even front porches for those who might want to wave at a neighbor.

This notion is not new to readers of American Bungalow. It is what we have stood for from the beginning, although I must admit we have featured a fair share of high-style craftsman dream homes, which I always rationalized with the belief that advertisers sell a lot more doorknobs to builders of such houses and that readers are always interested in what can be done by combining good taste with big bucks. Trophy homes notwithstanding, the word, “modest,” has always been a part of our creed. When it comes to houses, we feel that the design adage, efficiency is beauty, is especially true in today’s waste-conscious, “recycle it” world.

This new wave of recognition by the media is evidence that enthusiasm about our favorite home is not waning, in spite of the country’s hand wringing about home loans or overbuilding during the now-decaying housing boom. To the contrary, it appears as though the languishing economy is actually supercharging an already strong surge of interest in smaller, more efficient homes. In the mid 1990’s, the news was that there might be merit in “those horrid little houses.” Now, with the proliferation of interest in the craftsman style and the word “bungalow” restored to a positive connotation, the media’s rediscovery of the bungalow and bungalow neighborhoods focuses more on practicality than on style.

With so much of the American landscape bespattered with evenly spaced McMansions that seem to have dropped from an alien sky, it is comforting to recognize that the hammering of nails through green 2×4’s is now silent while we turn to recognize the merits of a tried and proven concept of home that we already have. For a while, at least, the pendulum of popularity has reversed, and American excess has been replaced by an interest in American efficiency.

Forum Member “Kevin in LA” needs your help!

This is from a home built in the Los Angeles area in the 1920′s:

“With the poppies and grizzlies, it’s probably only found in California.”

“With the poppies and grizzlies, it’s probably only found in California.”

Bob Winter, who has served American Bungalow with distinction since the days it was just a gleam in its founder’s eye, has been honored with the 2009 Los Angeles Conservancy’s President’s Award, here. In addition to his classic work with David Gebhard, cited in the award announcement, Bob authored The California Bungalow (Hennessey + Ingalls, 1980, still in print). Bob, and the book, were profiled in Issue No. 49 on the 25th anniversary of its publication. Our sincerest congratulations to a dear friend.

The Editor

For some years now, I have toyed with the idea of offering an article in American Bungalow about the importance—and the romance—of railroad transportation during the original bungalow era. Photographer Alex Vertikoff and I have even gone so far as to shoot photos for such an article, or at least we did whenever the subjects fell into our laps. It can be remarkably heady stuff. Many of the depots and train stations were created in the Arts & Crafts style, as were some of the era’s private Pullman cars. And anyone who has been near a steam locomotive knows of the awesome power, virtually and literally, these icons of our past can project. Then there is the personal aspect of it all – the way 20th Century America’s trains provided an up-close, mile-by-mile insight into the landscape—participation, really—and allowed travelers to actually get to know each other in the process.

But it is often difficult to discern what is objectivity and what is sheer fancy, and both Alex and I are known to wax fanciful when it comes to trains. It concerns me that readers who have waited three months for their magazine might not be thrilled to see some of its pages filled with material that, however well presented, in this day and age is not a part of their world. Conversely, in a time where our brains are invisibly penetrated by wireless waves, it might be refreshing to immerse one’s consciousness into the reality of wood and leather and iron and the hot, living breath of steam.

Fortunately, in this age we do have the Internet, so I thought I’d just ask, wirelessly. Your thoughts on including this content—or this kind of content—within the pages of American Bungalow are invited.

For that matter, I encourage your ideas and suggestions on all aspects of the magazine’s content. In magazine publishing as well as with railroads, it’s the squeaking wheel that gets the most attention.

John Brinkmann

Publisher/Founder

American Bungalow

Recent Comments