BY DONALD COVINGTON

This is the story of one manâs rise and fall, buffeted by the turns of economic fortune during his lifetime and nourished by an architectural style that would sweep through Americaâs cities.

The California Craftsman style was created in part by famous architects, and popularized by carpenters and independent developers. The elements of the style were used to achieve a form of home building which approached the status of folk art. It was a builderâs art form, a style that celebrated an aesthetic based upon the logic of forming a simple, forthright structure using natural materials. And, it was nurtured by the hands-on labor of many, many common craftsmen and builders.

One of those who created Craftsman homes in Southern California and as far north as central Oregon, in the years between 1900 and 1930, was David Owen Dryden. Born in 1877 on a ranch in the redwood forest of Sonoma County, Calif., Dryden later moved with his family to a farm on the southern Oregon coast. In his youth, he apprenticed with relatives in the lumbering and building trades, on the Pacific Coast, where he acquired firsthand a knowledge of wood structure, and sensitivity to the rustic quality of vernacular architecture and natural materials.

In the mid-1890s, at the age of 18, David Dryden moved with a sister and brother-in-law to the small orchard community of Monrovia, Calif., in the San Gabriel Valley, a few miles east of Pasadena. In that small foothills community, in 1902, David met and married Isabel Rockwood. Together, David and Isabel launched a career of home building and decorating. David created structures in the typical builderâs bungalow style of the day. Isabel collaborated with him on functional planning and chose colors and other enhancements of interior elements. As gardens were considered to be integral parts of the whole plan, Isabel chose plants and supervised the placement of landscape elements.

In Los Angeles, David worked odd jobs, including that of a Tram Conuctor on the Boyle Heights Line, Before becoming a carpenter in the thriving home building industry in the community of Monrovia

In their early years in Monrovia, the Drydens purchased building sites, completed structures and moved into them for the finishing phase. While David worked on a new house, Isabel turned a recently completed one into a functioning and artfully decorated home. As their reputation for creating handsome, stylish bungalows grew, they were constantly on the move from completed home to new structure. One year they moved eight times.

David Drydenâs aesthetics gradually evolved from the ubiquitous bungalow of the early 1 900s to the more romantic âchaletâ style, made popular throughout the San Gabriel Valley by the Greene brothers and their contemporaries. The Craftsman style that emerged in the first decade of the century turned the builderâs craft into an expressive art form, and often, as in Drydenâs case, made the house carpenter a folk artist.

By 1911, after a decade of developing his craft and mastering the new style, Dryden moved from Monrovia to San Diego where a building boom had begun in preparation for the 1915-16 Panama- California Exposition celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal. It was in the new suburbs of Point Loma, Mission Hills and North Park that the mature phase of Drydenâs Craftsman style developed.

Drydenâs San Diego houses affirm the harmony of shelter and earth through the combination of natural materials and structure, expressing the concepts of the Craftsman movement. Deep eaves supported by a variety of brackets and beams are capped by broad, low-pitched roof lines. The roof structure hovers above walls of redwood shingle and board siding, which occasionally rest on foundations veneered in river-worn boulders and cobbles.

The simple, direct forms of Drydenâs houses take on a dynamic character through the contrast of solids with the open structure of pergolas and port-cocheres. The picturesque effect is always present in the exteriors and is achieved by extruded elements such as stairways, window bays, inglenooks, balconies and sun porches. Shadows patterned by open structure and textured surfaces that evoke the natural character of the material add to those effects.

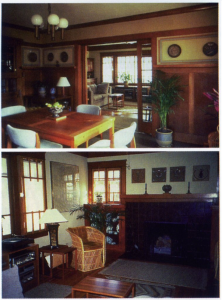

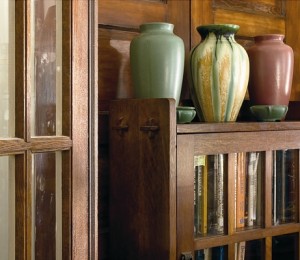

Interiors of the houses contain extensive wood paneling and cabinets with leaded art glass and glazed ceramic tile. Built-in buffets, china closets and bookcases in quarter-sawn oak or red gum are typical. The open plan is achieved by wide arches between major rooms or by double, sliding pocket doors and French doors. The integration of interior and exterior space is created by continuous lines of casement windows for maximum light and ventilation.

These houses, built in the years of the Exposition in San Diego, brought status and wealth to David Dryden who progressed from the role of a carpenter to that of an independent building contractor, supervising a crew of artisans and craftsmen. By the spring of 1915, at the peak of the San Diego building boom, Drydenâs mature Craftsman style had reached its zenith.

Drydenâs clientele steadily increased during 1916-17. His work flourished and he became known as a builder of Craftsman style houses and bungalows for the affluent new middle-class professionals and retired industrialists who, eager to escape urban congestion and colder Eastern climes, were eager to live in a genteel, semirural villa â surrounde d by orchards, gardens and lawns, a short tram ride away from the merc antile and commercial establishments of the urban center.

Creative by nature, David enjoyed the role of designer and director of construction; but he was impatient with record keeping and preferred to pay receipts from pocket cash. His lack of prudence in business affairs was matched by a disdain for money in general. Drydenâs descendants recall his throwing money away, literally, over the cliffs into the surf below.

His lack of respect for currency, however, did not extend to the luxuries that wealth could obtain. His obsession for quality in construction also extended to other material possessions. He admired fine tailoring and fast motorcars. He was a traveler as well, and spent many summers exploring the Pacific Coast by steamer and automobile, from the Mexican border to the rivers of Oregon.

And there was a gentler side, that David Dryden revealed in the poems he wrote for his grandchildren and in rhymed notes to his mother-in-law. Letters to his wife indicated a sentimental man of tender demeanor, and one with great admiration for the beauties of the natural environment. It was this more sensitive side of his nature that suffered most from the humiliating experience which followed the failure of his once robust career.

With the entrance of the United States into World War I in 1917, real estate and building businesses took a sudden nose dive. Shortages of man-power and materials made house construction a difficult and expensive venture. A national influenza epidemic also helped depress the economy. Dryden found it hard to gain enough commissions to ensure payment for the many high interest loans to which he was committed. With the need to cope with the ebbing tide of fortune that had once brought him wealth and security, Dryden apparently succumbed to questionable business practices and, eventually, to alcohol abuse.

A rash of liens and lawsuits for unpaid bills mounted against Dryden and, in the late winter of 1918-19, the Drydens left San Diego. Isabel and the children remained in the Los Angeles area while David returned to Oregon to recover emotionally and financially from the personal catastrophe which had devastated his life and career. He moved north to the Umpqua River where he worked with some success as a carpenter building houses and barns for $5.50 a day, a decent wage at the time.

By the winter of 1920-21, with new resolve and somewhat financially recovered, David and Isabel returned to San Diego where they began anew to acquire land for construction. The Craftsman style that had been popular the first two decades of the century had lost its appeal in the postwar years, however, and Dryden gradually shifted from the frame bungalow to the more modish stucco and tile âhacienda.â The Spanish Revival style, initiated by the seductive charms ofâ the lath and plaster palaces of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition and reinforced by Hollywood films, spread across the new suburbs of the 1920s, not only in San Diego but throughout California.

In the summer of 1925, the Drydens moved to the San Francisco Bay area, where David gained a second small fortune continuing to build stucco bungalows in the popular Mediterranean style. Drydenâs masterpieces, however, remain the romantic Craftsman villas and bungalows that he created in the years before World War I.

It is a tribute to the quality of his craft that most of David Drydenâs houses from his early career in San Diego are well-cared for today. Many of them, having survived modernizat ion and change, grace the old suburb and neighborhoods north of Balboa Park, echoing the serene lifestyle of a distant era.

While vacationing in Northern California during the summer of 1946, David Owen Dryden died on the picturesque Pacific coast that nourished his early aesthetic awareness.

Recent Comments