by Michelle Gringeri-Brown

Robert Magilligan came down from the Bay Area for a birthday party and bought a house. A brown shingled two-story Craftsman on a luxuriously wide street of similarly impressive homes, he believes his house was designed by Greene and Greene.

Robert Magilligan came down from the Bay Area for a birthday party and bought a house. A brown shingled two-story Craftsman on a luxuriously wide street of similarly impressive homes, he believes his house was designed by Greene and Greene.

“Although I wasn’t looking for a home at that time, when I saw a For Sale sign in front, I decided without hesitation that this was the only place I could live in Southern California,” he says. “Oaklawn was a magnificent turn-of-the-century neighborhood that had been mostly preserved, and it still retained its unique character. I bought the house with the interior sight unseen.” Never mind that that interior was 3,800 square feet and Magilligan, a soon-to-be-retired single accountant, already owned a condo in San Francisco, a second home in Marin and a converted schoolhouse in Napa. He sold them all, moved down to South Pasadena and became smitten with all things Greene and Greene.

It was an established fact that brothers Henry and Charles Greene had designed the South Pasadena subdivision’s layout, entry portals, border fence, and a few years later, a footbridge and waiting station. Neighborhood legend had it that four of the Arts and Crafts houses were unattributed Greene and Greenes. But Magilligan wanted to know more, and began researching the history of his neighbors’ homes. This led to a year of talking with professional and amateur historians, and digging through various archives in search of the Greene and Greene connection he grew to be certain was there. Ultimately, he compiled an illustrated 45-page document on his findings, which he hopes will prompt architectural scholars to delve even deeper

In 1904 Charles and Henry Greene began working with the South Pasadena Realty and Investment Company to develop an existing orange grove into a “Suburb de Luxe,” as a 1907 brochure trumpeted. The street was 75′ wide to accommodate an impressive old oak, and the architects designed two distinctive cobblestone portals to frame the tree from the development’s entrance. Cobblestone-and-clinker-brick seating surrounded the tree, which was intended as a neighborhood meeting place.

In 1904 Charles and Henry Greene began working with the South Pasadena Realty and Investment Company to develop an existing orange grove into a “Suburb de Luxe,” as a 1907 brochure trumpeted. The street was 75′ wide to accommodate an impressive old oak, and the architects designed two distinctive cobblestone portals to frame the tree from the development’s entrance. Cobblestone-and-clinker-brick seating surrounded the tree, which was intended as a neighborhood meeting place.

Magilligan found a 1905 Pasadena Tournament of Roses publication touting the charms of Oaklawn in an ad, with a Charles Greene article, “California Home Making,” just a few pages prior. Greene’s illustrations accompanied the feature text, and included a painting of an entrance portal just like the ones that lead into Oaklawn.

“Charles Greene wrote, ‘Under the foothills is a beautiful spot, overlooking the valley to the south, a quiet nook just above a grove of wide and spreading live oaks. North are the sloping vineyards and the mountains rising high above.’ This is a description of Oaklawn,” Magilligan says with conviction.

The Greenes were not commissioned to design the first four houses in the development, all of which were impressive, costly homes. But they were hired to build a bridge from the promontory of the neighborhood down to Fair Oaks Avenue, perhaps in an effort to make the location more appealing to middle-class buyers who would need to commute to work.

The bridge spanned two railroad tracks on the east side of the Oaklawn development, and connected the homes to Fair Oaks’ streetcar service and the adjacent Raymond Hotel and its golf course. The design that was selected was modern and built from a relatively new product: reinforced concrete. It included a cobblestone waiting station with a tile roof on the Fair Oaks end. Soon after it was finished in 1906, the bridge developed cracks and the railroads insisted that an additional pillar be installed, much to the architects’ chagrin.

“I first began researching the Greenes in 1954,” says Randall Makinson, director emeritus of the Gamble House, “and shortly thereafter met some of the Greene family, including Henry’s daughter, Isabelle. One of the first stories she and her husband told me was that the saddest thing in Henry’s life was the bridge. He took such great pride in it, and for the extra column to have to go in, that just crushed him, she said. Every time I saw her over the next 30 to 40 years, that story would get retold. Henry just talked about it all of his life.

“There is a photo from the family that shows sandbags on the bridge and the tests that were done proving that it was sound,” Makinson says. “The Greenes believed in it, yet the railroads controlled everything, and they had to yield to the railroads’ wishes. It was the third reinforced-concrete bridge in the U.S., the second in California and the first designed by an architect. They had every reason to be very proud.

“There is a photo from the family that shows sandbags on the bridge and the tests that were done proving that it was sound,” Makinson says. “The Greenes believed in it, yet the railroads controlled everything, and they had to yield to the railroads’ wishes. It was the third reinforced-concrete bridge in the U.S., the second in California and the first designed by an architect. They had every reason to be very proud.

“The Greenes showed the world that concrete could be a graceful construction material. The increasing spans — the first is small, the next larger, and so on — are a beautiful sculptural composition,” he says.

The bridge stood with its extra support for 90-plus years, then in 2002, the city of South Pasadena undertook a restoration of the structure. “When it came time to restore the bridge for a coming Metroline project, the city had the vision and the courage to have it checked by engineers and to form a committee to see to the accurate restoration,” Makinson, a member of the committee, comments.

“They replaced the missing back and seat in the waiting station — which someone had previously decided should become a gateway into the small park that adjoins it. I’ve noticed that people are sitting there now, waiting for the bus, which was its original intent and function. And interestingly, the contractors who removed the extra column found that there was an inch of separation between the added column and the bridge; it never was being held up by it.”

The Oaklawn bridge committee had to consider things like the grit of the sand in the original concrete, as well as the color and texture — all to make sure that the repaired sections matched perfectly. The ingredients for the paving on top of the bridge went through the same process. “Everybody, from the contractors on down, listened carefully to the committee’s suggestions,” Makinson says. “When missing segments of the railing had to be put in, they went to the extreme to get the planks that made up the concrete forms to be the same size and go in the same direction as when the bridge was built.”

Wrought-iron lighting fixtures for both ends of the bridge were designed by the Greenes but never installed. The drawings for the four lanterns that were intended for the obelisk on the Fair Oaks side were found recently by Edward Bosley, director of the Gamble House.

Wrought-iron lighting fixtures for both ends of the bridge were designed by the Greenes but never installed. The drawings for the four lanterns that were intended for the obelisk on the Fair Oaks side were found recently by Edward Bosley, director of the Gamble House.

“I uncovered the drawing of the unexecuted light fixture from among the Oaklawn drawings at Columbia University’s Avery Library,” Bosley says. “It is not a Craftsman design to be sure, but is nonetheless simple, dignified and wholly appropriate to the base on which it was meant to be affixed. The obelisk base itself is more forward-looking and unabashedly modern than the Greenes’ typical work, but so is the bridge, as it should be, especially when we consider that it is one of the very first reinforced concrete bridges in the United States.”

With the removal of the offending support, the bridge looks much as it did in 1906. “The Greene family is delighted with the renovation,” Makinson reports. “They said, ‘Grandpa would finally be happy!’”

In 1907 a financial downturn caused various sections of Oaklawn to be sold to other developers, including G.W. Stimson, who had found that to “maximize profits, it was best to sell a lot with a home constructed on it,” according to Magilligan’s manuscript. “At this time, the construction process was difficult … and financing was not available to individuals constructing residences. However, a completed home and lot could be readily financed with a mortgage. Alternatively, a buyer wanting to construct his own home was more inclined to purchase a lot if plans were included.”

Magilligan believes that Stimson hired the Greene and Greene firm to design six homes on Oaklawn in an attempt to bolster sales and present the public with architect-designed houses that would justify the high-priced lots. It is established that the Greenes did take on the interior design of one of the earlier spec houses, and Magilligan sees numerous similarities between its interior and those of the unattributed homes.

The six houses were considered moderately priced, ranging between $5,000 and $12,000. Each was different from the others and designed for its specific location. Magilligan’s research concludes that Stimson was required to use Peter Hall as the contractor, the same builder who constructed the gateways and fences surrounding Oaklawn, and that the Greenes’ involvement was over once the plans for “Oaklawn Series I—VI” were drawn.

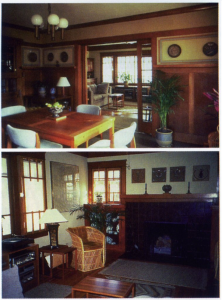

Bob Magilligan spent considerable time and effort taking his own home’s interior back to its period roots. His painter matched the original colors in the living and dining rooms, while he chose an appropriate but new-to-the-house green for the library. The Port Orford cedar wainscoting and trim in the dining room is painted with ivory enamel, an original finish specified in several of the homes

Bob Magilligan spent considerable time and effort taking his own home’s interior back to its period roots. His painter matched the original colors in the living and dining rooms, while he chose an appropriate but new-to-the-house green for the library. The Port Orford cedar wainscoting and trim in the dining room is painted with ivory enamel, an original finish specified in several of the homes

Magilligan’s house was built in 1909 for a cost of $9,500. It has art glass in its front door and in the swinging door to the kitchen, as well as leaded- and stained-glass light fixtures and sconces in the living room. The library’s fireplace has a carved inscription on the mantel: “Who Loves a Book Will Never Lack a Friend.”

His background as an accountant perhaps predisposes Magilligan to see the numerical patterns in various rooms: groups of three or four or five elements, repeated in molding details, window placement, art-glass designs and the like. Even if his amateur historical research isn’t borne out by the academics, Magilligan is sure his home is an architectural gem. “I always thought this house was going to be much simpler than the ornate Victorians I lived in before. But Craftsman houses are like a painting: when you start to examine them closely, you see that every brush stroke or detail is important and relates to the others.”

A zealous activist in his neighborhood, Magilligan preaches the Arts and Crafts doctrine and the talents of Charles and Henry Greene to all of his fellow homeowners, encouraging them to bring their homes back to period style. He is also working to fund the replanting of the street oak tree that either died or was removed after a traffic fatality — depending upon which neighborhood legend one believes. But whether they treasure their homes for their historical architecture, or simply find them comfortably livable houses, the residents of Oaklawn typically stay put 20, 30, 40 years or more.

A zealous activist in his neighborhood, Magilligan preaches the Arts and Crafts doctrine and the talents of Charles and Henry Greene to all of his fellow homeowners, encouraging them to bring their homes back to period style. He is also working to fund the replanting of the street oak tree that either died or was removed after a traffic fatality — depending upon which neighborhood legend one believes. But whether they treasure their homes for their historical architecture, or simply find them comfortably livable houses, the residents of Oaklawn typically stay put 20, 30, 40 years or more.

“Everybody knows everybody here,” Magilligan says. “When I lived in Pacific Heights [San Francisco], it was 10 years before I met my neighbors. Here there are retirees and families, and the kids have the run of the street. We throw parties for each new owner whenever one of the homes sells. It’s still a wonderful place 100 years after the Greenes designed it.”

Pin It

Starting with a simple 1904 bungalow that had seen its features get lost and confused over the years, we decided that our goal was to clarify our home’s style.We have put in wood floors and added a mix of original and reproduction Arts and Crafts furnishings, along with a collection of international folk art. We also “furnished” many “rooms” in our garden that surrounds our home, with ponds & fountains interspersed between over 1,000 species of plants crowded into our 50 by 100 lot. Our place, which we’ve named “The Trellises,” is an oasis in the midst of busy downtown.

Starting with a simple 1904 bungalow that had seen its features get lost and confused over the years, we decided that our goal was to clarify our home’s style.We have put in wood floors and added a mix of original and reproduction Arts and Crafts furnishings, along with a collection of international folk art. We also “furnished” many “rooms” in our garden that surrounds our home, with ponds & fountains interspersed between over 1,000 species of plants crowded into our 50 by 100 lot. Our place, which we’ve named “The Trellises,” is an oasis in the midst of busy downtown. This wonderful American Foursquare sits in the historic neighborhood of Irvington, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to hundreds of similar Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts—era structures. Constructed in 1906 as a private residence, the home also served as a fraternity house for Butler University in the 1920s.The exterior is clad in fieldstone and shake. A matching fieldstone fireplace and beautiful wood-beamed ceilings and woodwork make this an incredible home in which to dwell.

This wonderful American Foursquare sits in the historic neighborhood of Irvington, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to hundreds of similar Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts—era structures. Constructed in 1906 as a private residence, the home also served as a fraternity house for Butler University in the 1920s.The exterior is clad in fieldstone and shake. A matching fieldstone fireplace and beautiful wood-beamed ceilings and woodwork make this an incredible home in which to dwell. Our bungalow was built by the famous Detroit architect Leonard Willeke. We have all of the home’s blueprints in addition to many of Mr. Willeke’s original pencil drawings and letters. The correspondence he maintained with craftsmen and the original owners proves very revealing.

Our bungalow was built by the famous Detroit architect Leonard Willeke. We have all of the home’s blueprints in addition to many of Mr. Willeke’s original pencil drawings and letters. The correspondence he maintained with craftsmen and the original owners proves very revealing. Our home is a 1922 Craftsman bungalow that we and our two children have lived in for two years. Located in an historic section just north of Detroit, the house had fallen on hard times. Slowly though, we have made improvements. Oak hardwood floors abound upstairs and down and most of the original trim was thankfully left untarnished. The living room’s brick fireplace is flanked by built-in oak bookcases and works just fine on cold winter nights.

Our home is a 1922 Craftsman bungalow that we and our two children have lived in for two years. Located in an historic section just north of Detroit, the house had fallen on hard times. Slowly though, we have made improvements. Oak hardwood floors abound upstairs and down and most of the original trim was thankfully left untarnished. The living room’s brick fireplace is flanked by built-in oak bookcases and works just fine on cold winter nights. What started out in 2002 as a quest for the most affordable Craftsman bungalow in Pasadena ended up as a painstaking but revealing remodel. The remodeling turned out to be the education of a budding historian as he searched for clues to the beginnings of the house and its courtyard complex and the inspiration for its design and structure.

What started out in 2002 as a quest for the most affordable Craftsman bungalow in Pasadena ended up as a painstaking but revealing remodel. The remodeling turned out to be the education of a budding historian as he searched for clues to the beginnings of the house and its courtyard complex and the inspiration for its design and structure. Our 1916 bungalow is in the Springfield neighborhood, the largest residential National Register district in Florida. It was constructed by a local builder for a French-Canadian immigrant couple who lived here for 33 years. Before we bought it in 2006, it—like the neighborhood. which Southern Living magazine rated as the Number 1 Best Historic Comeback Neighborhood in the South in 2010—had gone through many downturns and upswings. But it has retained its original interior and exterior details.

Our 1916 bungalow is in the Springfield neighborhood, the largest residential National Register district in Florida. It was constructed by a local builder for a French-Canadian immigrant couple who lived here for 33 years. Before we bought it in 2006, it—like the neighborhood. which Southern Living magazine rated as the Number 1 Best Historic Comeback Neighborhood in the South in 2010—had gone through many downturns and upswings. But it has retained its original interior and exterior details. We bought our 1935 Arts and Crafts home in 2006 and have since restored it. It has four bedrooms and two baths, a living room with a fireplace, a dining room, and a kitchen and a small den. The house has typical Arts and Crafts molding and hardwood floors. We have enjoyed the complete renovation of this fine house.

We bought our 1935 Arts and Crafts home in 2006 and have since restored it. It has four bedrooms and two baths, a living room with a fireplace, a dining room, and a kitchen and a small den. The house has typical Arts and Crafts molding and hardwood floors. We have enjoyed the complete renovation of this fine house. We are the proud sixth owners and guardians of the historically design ated Laura A. Tyler House, built in 1913 in what is now Golden Hills, gust up the hill from downtown. We love our side-gabled Craftsman bungalow with its original fir floors, wide front porch. 10-foot ceilings, built-in cabnets, original windows and other fabulous architectural details, including a quirky one: the man who had the house built was a stove maker, and although the house has a chimney, it never had a fireplace.

We are the proud sixth owners and guardians of the historically design ated Laura A. Tyler House, built in 1913 in what is now Golden Hills, gust up the hill from downtown. We love our side-gabled Craftsman bungalow with its original fir floors, wide front porch. 10-foot ceilings, built-in cabnets, original windows and other fabulous architectural details, including a quirky one: the man who had the house built was a stove maker, and although the house has a chimney, it never had a fireplace.