by David Cathers

In East Aurora, a woodsy small town about 20 miles southeast of Buffalo, N.Y., the Roycroft Campus faces east onto Main Street. The rectangular Campus is bounded on one side by South Grove Street, site of the Roycroft Inn. Its western edge is a stretch of Oakwood Avenue, and one long block of Walnut Street defines its northern border. Number 46 Walnut Street is in the middle of this block. It is a part shingle-sided, part half-timbered house with a large skylight and is the former home of one of the most gifted and best-known painters ever to work for Elbert Hubbard’s Roycroft — Alexis Fournier.

Originally a barn where carriages were kept, the structure was converted into a house in about 1903 by a team of Roycroft carpenters. It stands on land that Hubbard gave Fournier as part of his campaign to persuade the painter to settle in East Aurora and take on the role of Roycroft artist-in-residence.

Behind the house is a small wood frame structure that was once a chicken coop and blacksmith shop. Remodeled by the Roycroft carpenters, it became Fournier’s studio. About 1910 he expanded it further, adding snug but comfortable living quarters on the first and second floors and affixing wooden trellises to the outside walls.

Color-drenched flower gardens fronted Fournier’s cottage, vines climbed the trellises and wreathed his studio skylight and an apple tree grew through the opening that he cut in the roof of his porch. As the art historian Laurene Buckley has written, Fournier named this idyllic but somewhat haphazard little building the “bungle-house,” because, he said, “it didn’t deserve to be called a bungalow.” After his death in 1948 the bungle-house gradually declined.

Color-drenched flower gardens fronted Fournier’s cottage, vines climbed the trellises and wreathed his studio skylight and an apple tree grew through the opening that he cut in the roof of his porch. As the art historian Laurene Buckley has written, Fournier named this idyllic but somewhat haphazard little building the “bungle-house,” because, he said, “it didn’t deserve to be called a bungalow.” After his death in 1948 the bungle-house gradually declined.

In the mid-1990s Boice Lydell bought the ailing building and began to bring it back to life. Though restoration is an ongoing job, today Alexis Fournier’s modest Arts and Crafts studio/cottage has a new identity: it is the home and central repository of what Boice has named the Roycroft Arts Museum.

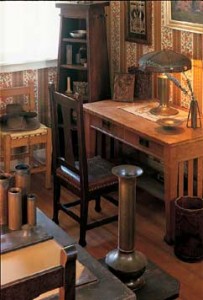

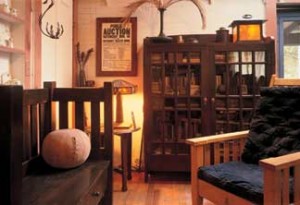

This is his private assemblage of more than 100,000 historic Roycroft and Roycroft-related objects: books; furniture; copper and other art metalwork; paintings, drawings and graphic works; leatherwork; pottery; sculpture; photographs; and what seems like an endless amount of archival materials, ephemera and memorabilia. How this unparalleled collection came to be is in part a story about families, and it is also a story about a young boy’s innate predisposition that grew to become his all-consuming passion.

To Grandmother’s House

Roycroft is literally in Boice Lydell’s blood. His great-uncle, Ernest Simmons, began his Roycroft career as Elbert Hubbard’s secretary and became the firm’s chief salesman after Hubbard died in the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania. For about 20 years, Simmons traveled back and forth across the country, calling on retailers and selling Roycroft goods. He loved his job and, says Boice, “He loved the Roycroft.”

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing until the 1960s, Simmons collected products once made by the now-defunct firm. Looking back, Boice says, “I remember being in his house when I was a little boy and loving the Roycroft books and all the other Roycroft things.” More recently, because of a lucky find, Boice learned that his maternal grandfather, M.G. Schneckenburger, was a local professional photographer whose clients included the Roycroft. Schneckenburger was also a hobbyist cabinetmaker, and an example of his work, a Roycroft-like fall-front desk with actual Roycroft hardware, is now in Boice’s collection.

These were not his only family connections to the Roycroft. Growing up he and his parents visited his grandmother in East Aurora about every two weeks. The route to her house went past the Campus, and he vividly recalls that he could not stop looking at the big, dark stone “Gothic-like” Roycroft buildings that this little boy found irresistibly “exciting and intriguing.” Like many children who grow up to become antiques collectors, he was naturally drawn to old artifacts from a very young age, even if he didn’t know exactly what they were or understand quite why he liked them.

These were not his only family connections to the Roycroft. Growing up he and his parents visited his grandmother in East Aurora about every two weeks. The route to her house went past the Campus, and he vividly recalls that he could not stop looking at the big, dark stone “Gothic-like” Roycroft buildings that this little boy found irresistibly “exciting and intriguing.” Like many children who grow up to become antiques collectors, he was naturally drawn to old artifacts from a very young age, even if he didn’t know exactly what they were or understand quite why he liked them.

Boice’s grandmother died when he was 14, and he asked his parents if he could have some of the things that he had found in her house. And so he inherited the beginnings of a collection: a few pieces of Roycroft copper, some Roycroft books and a Roycroft piano bench.

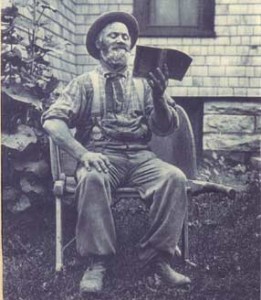

The most fascinating object of all, though, was a book written by Elbert Hubbard and published by the Roycrofters in 1899. It was called Ali Baba of East Aurora, a “biography” of Anson Blackman, the rough-hewn hired man and horse handler who worked for Hubbard and was dubbed “Ali Baba” by Hubbard’s oldest son, Bert. Reportedly, a thousand copies of that book were printed but this one was unique. It had originally been Ali Baba’s personal copy and he had inscribed his name in it.

In his mischievous writings in the Roycroft magazine The Philistine, Hubbard often “quoted” Ali Baba. On the printed page he transformed this unremarkable family employee into a colorful and largely fictitious local character who, among other things, was said to be a deep thinker, witty iconoclast, pungent philosopher and “head of the Motto Department.” Some of the attention-grabbing and at times racy phrases that Hubbard used to spice up his prose were said to come straight from Ali Baba’s mouth, though in fact they came from Hubbard himself, or, anonymously, from some of Hubbard’s buddies. As one of Ali Baba’s supposed sayings had it, “Every man is a damn fool for at least five minutes every day. Wisdom consists in not exceeding the limit.” When he inherited his copy of Ali Baba of East Aurora, Boice learned that Anson Blackman was his great-great uncle. That signed book, and the realization that he descended from Roycroft family, set the course of Boice Lydell’s life: at the age of 14 he vowed to create the ultimate Roycroft collection.

Antique-Worthy Home

When Boice was 15 he started dealing in antiques. He set up shop in Ashville, a small town near Lake Chautauqua in the southwestern tip of New York State, and began stocking up on merchandise found at local house sales. Long before the current Arts and Crafts revival got under way, he was buying Roycroft books for 25 cents apiece, Roycroft hammered metal bookends for 75 cents and Roycroft candlesticks for, at most, a dollar. Seasoned dealers mocked his foolishness: “What are you buying that junk for?” they would ask. “Nobody wants that!”

When Boice was 15 he started dealing in antiques. He set up shop in Ashville, a small town near Lake Chautauqua in the southwestern tip of New York State, and began stocking up on merchandise found at local house sales. Long before the current Arts and Crafts revival got under way, he was buying Roycroft books for 25 cents apiece, Roycroft hammered metal bookends for 75 cents and Roycroft candlesticks for, at most, a dollar. Seasoned dealers mocked his foolishness: “What are you buying that junk for?” they would ask. “Nobody wants that!”

Boice in fact bought all sorts of things and soon established himself as a successful general-line antiques dealer. He narrowed his focus in about 1990, and still buys and sells Victorian furniture and also 19th-century American folk art and painted country furniture; in his own home he lives with antique painted furniture. He continues to deal in and collect antique Oriental art objects and he also owns a huge collection of hand-forged, early American tools. But during his years of general-line dealing Boice was always on the lookout for Roycroft.

By the mid-1980s Boice’s Roycroft collection had grown so vast that it exceeded his capacity to house it. So he began collecting buildings. He first bought the former Roycroft shipping building, erected on the Campus in 1918-19, and stored his collection there. But he hadn’t become a collector just to keep things packed away. So he bought Fournier’s bungle-house and created room settings to display many of the Roycroft art objects he had amassed over the years. Boice now owns five of the Campus’ 13 National Historic Landmark buildings and he is working to retrieve Roycroft artifacts original to this site and get them back into Campus buildings. Recently, on the day he describes as the second most exciting day of his life, he found and bought the woodworking machinery — including a tenoner, shaper, ripsaw and two planers — that hummed in the Roycroft furniture shop during Hubbard’s day. He is now making plans to reinstall this machinery, get it running and bring in craft workers to put it to use.

Because Boice has always lived near East Aurora, he has often been able to buy Roycroft objects from their original owners and in many cases from the descendants of Roycroft artisans. Being local has given him an enviable edge, but, more importantly, it has broadened and deepened his appreciation of all things Roycroft and honed his keen collector’s eye. As he says, few Arts and Crafts enthusiasts today are able to examine a Roycroft piece and discern the hand of the person who made it. This leads to the common assumption that “Roycroft is simply Roycroft,” though Boice quickly counters that easy generalization with an emphatic “Not really!” It is true that Elbert Hubbard was the charismatic mastermind and astute consumer-products marketer who brilliantly exploited the Roycroft brand. But it was his highly skilled, individual artisans who created the firm’s distinctive handicraft wares.

Because Boice has always lived near East Aurora, he has often been able to buy Roycroft objects from their original owners and in many cases from the descendants of Roycroft artisans. Being local has given him an enviable edge, but, more importantly, it has broadened and deepened his appreciation of all things Roycroft and honed his keen collector’s eye. As he says, few Arts and Crafts enthusiasts today are able to examine a Roycroft piece and discern the hand of the person who made it. This leads to the common assumption that “Roycroft is simply Roycroft,” though Boice quickly counters that easy generalization with an emphatic “Not really!” It is true that Elbert Hubbard was the charismatic mastermind and astute consumer-products marketer who brilliantly exploited the Roycroft brand. But it was his highly skilled, individual artisans who created the firm’s distinctive handicraft wares.

Roycroft Family

In pursuit of building his collection, Boice has been able to track down a few of these Roycroft workers, or, more usually, their descendants. For instance, he bought pieces from the family of Henry Unverdorf, once the Copper Shop’s chief spinner, and the descendants of the copper worker Henry Wilson sold him Wilson’s tools as well as the pieces Wilson left unfinished. Some things in Boice’s collection came from the family of the designer and head of the Modeled Leather Department, Frederick Kranz. In the 1980s Boice interviewed Helen Willson Ess, then the last surviving Roycroft leather modeler. She explained the exact steps that she and the other members of her department followed when they cut and modeled leather and she agreed to deposit her original leather-working tools in the museum’s collection. (Part of this interview is reproduced on page 102 of Head, Heart and Hand.)

In pursuit of building his collection, Boice has been able to track down a few of these Roycroft workers, or, more usually, their descendants. For instance, he bought pieces from the family of Henry Unverdorf, once the Copper Shop’s chief spinner, and the descendants of the copper worker Henry Wilson sold him Wilson’s tools as well as the pieces Wilson left unfinished. Some things in Boice’s collection came from the family of the designer and head of the Modeled Leather Department, Frederick Kranz. In the 1980s Boice interviewed Helen Willson Ess, then the last surviving Roycroft leather modeler. She explained the exact steps that she and the other members of her department followed when they cut and modeled leather and she agreed to deposit her original leather-working tools in the museum’s collection. (Part of this interview is reproduced on page 102 of Head, Heart and Hand.)

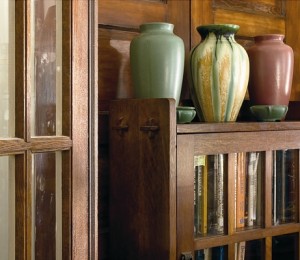

Also in the 1980s Boice bought original artwork from Dard Hunter II, whose famous father, the designer/artisan Dard Hunter, nearly single-handedly shifted the Roycroft visual vocabulary away from its Gothic-inspired roots and toward the clean-line, cutting-edge aesthetics of early-20th-century Austrian designers. Over the years Boice has been able to acquire extremely rare, often one-of-a-kind examples of Hunter’s artistry: a copper-and-leaded-glass cylindrical wall sconce made for the Roycroft Inn, more than 30 of Hunter’s drawings and several examples of his hand-wrought jewelry. He even owns some pieces of the molded pottery Hunter made at the Roycroft; fewer than 20 of these highly coveted vases are known to survive today.

It was, however, Boice’s contacts with the children of Roycroft metalworker Walter Jennings that has had the greatest impact on him. This phase of his collecting began in early 1998 when he bought a Roycroft bench that Jennings had converted into a worktable to use at home. His curiosity piqued by this purchase, Boice began buying vases, porringers and desk sets made by Jennings and was then able to acquire Jennings’ tools at an estate auction held by the master metalworker’s children.

It was, however, Boice’s contacts with the children of Roycroft metalworker Walter Jennings that has had the greatest impact on him. This phase of his collecting began in early 1998 when he bought a Roycroft bench that Jennings had converted into a worktable to use at home. His curiosity piqued by this purchase, Boice began buying vases, porringers and desk sets made by Jennings and was then able to acquire Jennings’ tools at an estate auction held by the master metalworker’s children.

Still not content, he bought two notebooks filled with photographs of Jennings’ work — after buying them he discovered that the photos were shot in M.G. Schneckenburger’s studio — and then he bought 13 loose-leaf volumes of Jennings’ drawings of his own designs. “Probably my most exciting day as a collector,” says Boice, “was the day I opened Walter Jennings’ notebooks. I had in my hands his drawings of every piece he ever made and his notes on when he made them and where he sold them. The information there was a historian’s dream come true. Heaven on earth.”

Boice confesses that he is passionate about Walter Jennings, and this passion has pushed him to reassemble Jennings’ entire home workshop: drawings, photography, jewelry and metalwork, tools, toolbox, wooden molds, the cigar boxes Jennings kept bits and pieces in, work gloves and, of course, the work table that sparked his fascination with Jennings in the first place. His collection includes not just an unparalleled number of superbly handcrafted Jennings-made vases, but many unique pieces as well. These include a pair of bookends on which Jennings, who had not yet begun signing his own work, inscribed “I made these in 1913.”

The collection also includes an exquisite silver bowl that he made for one of his daughters and decorated with the words “Isabel Warren Jennings Her Bowl 1916″ delicately hand-embossed around the rim. On its underside, the bowl is signed “W.J.” and “By Daddy.” Boice can authoritatively say, “Walter Jennings was the best chaser — detailer — in the Roycroft metal shop.” By collecting and studying not just Roycroft products but also searching out and studying primary source materials such as Jennings’ notebooks and workshop, Boice has almost certainly learned more about the working processes of Roycroft artisans than anyone alive today. “Collecting the information,” he says, “has become just as important as collecting the objects.”

Collecting in Depth

And yet collecting the objects is probably what Boice does best. The depth of this collection may be what most sets it apart. Though the trove of archival materials and ephemera cannot be captured in a photograph, for instance, it seems almost endless. But it is the sheer jaw-dropping uniqueness of so many objects in this collection — the realization that there are things here that you’ll never see anywhere else — that makes a visit to Fournier’s former bungle-house such a dazzling experience.

A few examples prove this point. Any collector would be thrilled to have one of the printed bookplates that Dard Hunter designed for Elbert Hubbard; Boice owns the original pencil drawing that Hunter did for that bookplate. The Roycroft edition of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature, with its Dard Hunter title page, would be an equally exciting addition to any Arts and Crafts collection; Boice has that original pencil drawing, too.

A few examples prove this point. Any collector would be thrilled to have one of the printed bookplates that Dard Hunter designed for Elbert Hubbard; Boice owns the original pencil drawing that Hunter did for that bookplate. The Roycroft edition of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature, with its Dard Hunter title page, would be an equally exciting addition to any Arts and Crafts collection; Boice has that original pencil drawing, too.

He has not only a wide-brimmed Stetson that shaded Hubbard’s head when he went out riding on his horse, Garnet, he also has the Stetson that Hubbard’s daughter Miriam wore when she rode beside her father. Like many collectors, Boice owns modeled leather bookends, table mats and other leather wares made and marketed by the Roycrofters; yet he also owns the gorgeous, one-of-a-kind tooled leather frieze panel made specially for the office of Hubbard’s wife, Alice.

A Roycroft Morris chair is another object that many collectors covet; usually constructed of oak or mahogany those chairs rarely come onto the market. Boice owns something much rarer: one of perhaps five bird’s-eye maple Roycroft Morris chairs made solely for the Roycroft Inn (though Hubbard may have had a few more made for special friends), this one with its original velour cushions still intact.

There is another side of Boice Lydell that not many people know about. He is a passionate expert in martial arts and has a black belt in karate. Martial arts may seem far removed from the world of antiques but not so: successful collecting is hardly ever a contact sport, but like karate it requires intensity, focus, strength, constant practice, physical and mental agility and an ever-competitive spirit. “I love collecting,” Boice says, and no one could doubt him.

Period images courtesy Boice Lydell

Recent Comments